Also, the American ideal of freedom has always been entangled with many other circumstances and preoccupations and ambitions. It was often conveniently forgotten when it came down to how certain people were to be treated; the tragedy was that the U.S.A. often proclaimed this ideal most loudly when it was also generating complex protocols for dodging its implications. It is astonishing that the phrase “all men [human beings] are created equal” was articulated in a society where so many men claimed proprietary ownership over other men.

Slavery eventually ended, but racism remains a corrosive force among us. Black people still experience deeply entrenched complex networks of discrimination and a burdensome spectrum of specific difficulties—the damage and the unhealed wounds of current and historic racism in America still greatly hinder black people and black communities from breaking out of the spiral of poverty and moving toward a life of fully human freedom and dignity. The injustices and inequities of racism must be faced in the U.S.A. This task is not an easy one, but it must be taken up by all our people with commitment and realism.

Its pursuit is a matter of the common good of the whole American people—indeed, the “American people” cannot flourish or mature as a people without an ongoing and courageous effort to regenerate and cultivate the landscape of community throughout our country. We must recognize and work together to repair the cracks and fissures of divisions and oppression that have played an ongoing part in the complex process of forming the history of what is still (relatively speaking) our young nation. We cannot evade or ignore the need for healing that manifests itself so clearly in our own time. If these injustices and wounds are permitted to fester in our society unattended, they will only grow into larger gaping holes swirling with the winds of violence and inviting new and further dehumanizing forces of ideology offering pseudo-solutions that will only make things worse.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. recognized that this nation needed a more profound commitment to justice, but he was determined not to answer violence with more violence. He sought to break the cycle of violence—the endless generation of oppression and resentment—through his historic nonviolent protest movement in the 1950s-1960s. In the process, Dr. King touched upon ways of being and acting that were relevant to the whole scope of human life. Though his legacy will always be primarily the fight against racism, Dr. King introduced the practice of nonviolent protest in a way that has been taken up by many social movements in the U.S.A. and around the world. This is not surprising. King realized that racism endures—as do so many human social problems—because of its foundation in the failure to recognize that every human being is a person. The whole multifaceted crisis of isolation and disintegration and the perpetuation of violence among individuals and between groups is a crisis of the human person.

Everyone speaks of "human rights" but no one seems to know what it means to be human, or why human beings have a value that demands respect, a value that deserves to be cherished, fostered, cultivated, defended, loved.

We are very far indeed from recognizing first and above all that each and every human person possesses a unique and ineradicable dignity which has its origin in something beyond the powers of this world, beyond any mere social consensus or political expediency.

Every human person possesses the dignity of being created in the image and likeness of God. Dr. King was emphatic about this point, and it is one of the keys to his ongoing relevance for the entire political project of the U.S.A., or for any nation that aspires to represent a genuinely free people. “Human dignity” is not a political or social construct. It is founded on a Source that transcends the whole world, but also impresses a stamp of inviolable identity and ineradicable value on every human person. Dr. King made this clear when he said: "The whole concept of the Imago Dei or the Image of God, is the idea that all men have something within them that God injected. This gives him a uniqueness, it gives him worth, it gives him dignity. We must never forget this. There are no gradations in the Image of God. Every man from a treble white to a bass black is significant on God's keyboard, precisely because every man is made in the image of God. One day we will learn that. We will know one day that God made us to live together as brothers and to respect the dignity and worth of every man."

Dr. King focused on the theme of the U.S.A.’s founding document—the Declaration of Independence—according to precisely that “evident truth” that must not be obfuscated or eclipsed if we want to be a society that respects human dignity and human rights: “All are created equal, and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights…” Humans are created persons, and their inherent dignity as persons and their rights as persons are given to them by God, who creates them in His image. The American Founders themselves missed the full implications of what they declared here (and thus slavery and racism continued). It would be “four-score-and-seven years” before a U.S. political leader would effectively propose a more profound examination of these founding principles.

A century later, Martin Luther King would challenge his country to go even deeper, to take a further step in an effort to be a nation of persons who are given-to-themselves, radically—who have rights, indeed, to live in the dignity of God’s image, to be free as persons, and to pursue their destiny, their need for fulfillment, for “happiness.” Dr. King realized that the implicit exigency of this declaration projected the actualization of these “human rights” and this freedom as love—love for the God who makes us and directs our history, and love for one another as children of God, as brothers and sisters.

What Dr. King asked from the government was not that it force humans to love one another, but that it would attend to removing the obstacles to freedom that were entrenched in society, the injustices that imposed suffering, encouraged divisions and resentment, and fostered a forgetfulness of our common humanity.

Here I believe that Dr. King—taking up the struggle against racism in the light of the Gospel’s proclamation of grace and redemption—caught a glimpse of how God’s saving love can penetrate and shape even our temporal hopes and aspirations, thereby enabling us to see and to build up the good in this world, to have a society more fair for everyone, more helpful, more loving, more willing to share burdens on the journey of this life toward its ultimate fulfillment.

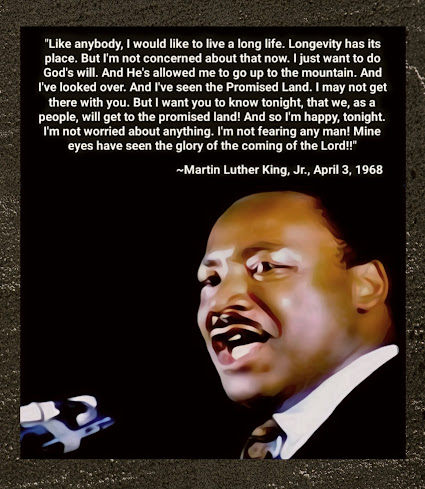

And we must struggle against social evils and injustices, not in the hopes of building a utopia, but because we who are made in God’s image are called to do God’s will—which is his mercy. The effort to make society better involves the works of mercy, and perhaps looks forward to something like a “culture of mercy” or a “civilization of love” (as Saint Paul VI envisioned it). Here I am trying to see from my own place on the mountaintop something that corresponds to King’s “Promised Land” image that he referenced in his final speech the night before his death—and I see a Gospel-inspired ideal of an entire temporal social order full of the plea for mercy, for peace, of aspirations and attainments of unity, mutual esteem, and solidarity. As a Catholic Christian, I am guided by the consistent teaching and vision of all the Popes in my lifetime, beginning with Saint John XXIII’s Pacem in Terris and developing through the Second Vatican Council to Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis in the present day.

Much of Dr. King’s vision is congruent with the larger aims of Catholic social teaching. King was familiar with the “personalistic” and “communitarian” implications of the Gospel. As he put it, “ ‘I’ cannot reach fulfillment without ‘thou.’ The self cannot be self without other selves. Self-concern without other-concern is like a tributary that has no outward flow to the ocean.”

The dignity of being created in God's image, of being a person, is lived and fulfilled in relationship to other persons. I can only discover "myself" through the gift of myself. We exist in relation to one another, and we realize ourselves in the living affirmation of "being-in-relationship." We fulfill ourselves by caring for one another, by taking responsibility for one another, by living the relationships with the persons who have been given to us.

The dignity of being created in God's image, of being a person, is lived and fulfilled in relationship to other persons. I can only discover "myself" through the gift of myself. We exist in relation to one another, and we realize ourselves in the living affirmation of "being-in-relationship." We fulfill ourselves by caring for one another, by taking responsibility for one another, by living the relationships with the persons who have been given to us.

People today speak so much about freedom, and we think we know that "freedom" means being able to choose for ourselves without being coerced or suffocated by some extrinsic power, whether private or public. But this does not mean that freedom is pure indifference, without purpose. Freedom has a meaning that comes from within itself. It is written upon our hearts.

Freedom does not exist to affirm itself, or to simply lose itself in a blind connivance with psycho-physical urges, forces, and drives within the person. All our human energies are meant to be directed by an adequate vision of reality—a wisdom—so that the whole person might be opened to self-giving love and adhere freely to what is good, to what brings authentic human flourishing and leads to happiness.

Freedom is made for the giving of self. Through freedom the person exists as a gift, the "I" lives in relation to the "Thou." This common unity blossoms into a solidarity that discovers more relationships to others and awakens more love.

It leads to "community"—communion-of-persons in love.

We are challenged to "let freedom ring"—to live our freedom by choosing to affirm the dignity of every human person, choosing to give ourselves in love, choosing to live in communion with God and with one another. The Christian knows that such choices are empowered by the grace of Jesus Christ. We enact an affection for humanity that is born in us when we encounter Jesus and experience his love for our humanity. We can live in a “secular society” as passionate witnesses to this encounter with Jesus and the fullness of life he gives us in his Church, while respecting the freedom of others who search for meaning, goodness, and truth. We can work with them for the common good of this country without compromising or watering down our faith. We can be evangelizers and honor the freedom of everyone, because the goal of our witness is not to manipulate people into becoming partisans of an ideology that compromises their humanity. We know that Christ is the fullness of freedom and humanity for every person, and we want to live and share this conviction with everyone.

But in so doing, we also entrust all our efforts to the infinite mercy of this loving God who in Christ has “already” embraced every person. We know that the ways of God are mysterious, and that Christ who is the Lord of all can awaken and draw our non-Christian friends “secretly” in the ways of his love and healing—until the day that they finally meet him in his fullness. In society, we Christians ask not for earthly power, but for the freedom to witness to the Gospel, placing our trust in the Holy Spirit for the fruitfulness of this witness according to God’s plan, and in God’s time. Not knowing the deepest interior dispositions of others, we have no reason to feel superior to them. We can always take the lowest place, and choose to follow Christ by seeking his face and serving him in everyone.

The confidence of Martin Luther King Jr. was founded upon his encounter with Jesus Christ, and the conviction that he was called to serve God on a very particular path. His hope was that this world through which we journey in this temporal life might even now reflect more fully “the glory of the coming of the Lord” who is our final destiny, who is greater than all our fears and all our efforts, who is greater than death, who is Infinite Love. Dr. King formed many ideas and specific proposals in his efforts to live out his vocation, and they certainly had an enduring impact on our history that will continue to unfold in the future. But most importantly: in everything he strove to uphold the ideal of nonviolence, because he “just want[ed] to do God’s will”—especially as revealed in Jesus’s words, “love your enemies.” This kind of love—this active mercy in engaging the problems of this world that loves even the enemy and never gives up the struggle and the hope that the enemy might be changed and become a friend—is a choice that God’s gift of himself in Jesus Christ has made possible for our freedom.

We can choose to cry out from our hearts to the One in whose image we are made, to seek goodness and love, to share our lives, to respect one another, to help one another, to live in peace with one another. Or we can choose to horde ourselves; we can choose to live according to our whims, our impulses, our narrow perceptions, our prejudices, our fear. But then we will reap a harvest of violence, and more violence.

Martin Luther King, Jr. remains important to our history today, reminding us of what it means to be human persons, to give ourselves, to live as children of God, as brothers and sisters.

His legacy remains with us, to remind us to be free, to remind us of the drama and responsibility of freedom, and of the promise that awakens freedom and draws it (and us) toward the happiness of communion in the One in whose image we have been created.