It is Easter Week for Orthodox Christians all over the world, including those who live in various politically independent Eastern Slavic nations.

We are not called to judge the heart. God alone sees the heart. So there is no sense in trying to imagine how anyone could participate in the Divine Liturgy of Great and Glorious Pascha on Sunday, while holding in his or her heart plans to murder, rape, or force into exile his or her Orthodox Christian brothers and sisters on Monday. Or any other persons who share the humanity of Christ. God have mercy on us all. This is the most direct reflection I can offer right now about the war in Ukraine.

On the other hand, those who are the victims of war experience another kind of “challenge” in celebrating Jesus Christ’s victory over sin and death. They are crying out for a “savior,” for whom they feel an immediate, visceral, concrete need. They are broken not only by their own sins, but also by the wounds inflicted upon them by the violence of others. How do they find the voice to sing “Alleluia” in the midst of these ruins, and in the expectation of more destruction still to come from their relentless oppressors?

These questions arise in many hearts this Easter—questions that are conscious and urgent especially in people who are suffering in the midst of the brutality of the war of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, as well as other people who suffer because of any of the seemingly-irresolvable conflicts of various kinds that rage all over the world today. But these questions would remain—along with so much loss, injury, trauma, and multiple needs for healing—even if (God willing) these afflicted people were to be rescued tomorrow, or if some kind of peace allowed them to live once again in freedom and without danger in their own nations, or (depending on the level of interpersonal or communal violence they have endured) to live in security and tranquillity and at least the hope of an equitable restoration of what they have lost. In any case, they might find it difficult to appreciate the meaning of “salvation through Jesus Christ” (words which are so easy for us to say) when they are looking for clean bandages, or food, or help with crippling PSTD.

They won’t get very much help from “words about” the resurrection, spoken carelessly at a distance. They need us to help them, to stay with them, to listen to them, to accompany them… somehow. We need to remember our brothers and sisters in their sorrows, even if we are not in a position to “do” anything else for them at this time. I can’t “do” much for them, but my heart is with them; in the circumstances of my own relatively mild but insuperable restrictions, my heart is with them, in my poor “solidarity” which I sustain as best I can. I’m pondering and trying to express what they need, which is a kind of “solidarity,” and it is also inseparable from what I really need, what every human person needs.

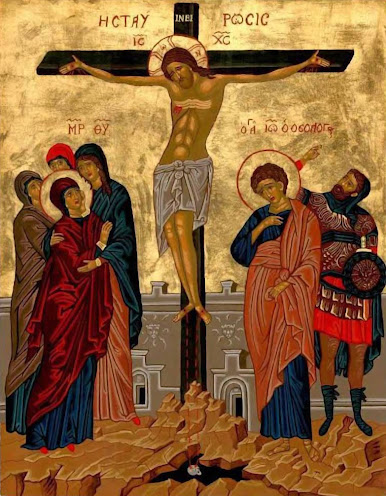

We need to be saved by the Word Incarnate, because we are bodily beings. Jesus makes it very clear to the disciples that He is not a ghost. He is transformed but totally, concretely human. He is a man with a body—the same man the disciples knew before—who has conquered sin and death and evil. He is glorified in His humanity, which is a mystery, but one that gives “more weight” to this real humanity rather than detracting from it. Here it is important for us to see that the Risen Lord does not “undo” His crucifixion; He rises with His wounds (hands, feet, side) in His glorified body, wounds transfigured by Divine Mercy, to be forever signs of His forgiveness.

For the victims of war—and in often hidden ways for all of us, because we all have wounds and we all hurt one another—the disfigurement, the pain, the bitterness, and the anger may last long after the wounds become scars. But we who have been wounded must not allow ourselves to be reduced and defined by these scars on our bodies and/or on our memories—to allow them to diminish our adherence to the truth about our lives in our relationship to our destiny, the fulfillment of our true selves which has already begun, and is already shaping us in the present moment.

The Risen Jesus shows us His wounds, and reveals to us that our own wounds have meaning. The Kingdom of God manifests itself, the world begins to be transformed into the New Creation, when—in union with Jesus crucified and risen—we forgive those who have injured us, we love our enemies, we pray for our persecutors. This does not mean we ignore injustice, trying to pretend the wounds are not there. What we seek is the conversion of our enemies—not only that in their sorrow they might try to repair what they can of the damage they have done to us—but fundamentally that our enemies might become our friends, together with us in the Body of the Risen Lord, united in His forgiveness that brings new life—eternal life.

This is an unimaginably difficult attitude to expect from anyone whose city has been bombed, whose family has been raped and killed and buried in unmarked graves, whose cultural heritage has been trampled underfoot and whose entire people have been targeted—whether by the bullets or other simpler tools of mass executions, or by indiscriminate bombing (whether nuclear or “conventional”), or by poison gas, or by artificial famine, or (more subtly) by a “re-education” that brainwashes them into forgetting their cultural memory or at least forces them to conform. Survivors and resistors of such things understandably might wonder: “Forgive our enemies? What does that mean?”

It means many profound things. But it begins with the determination never to cease respecting their enemies as persons, who possess fundamentally an inherent, gratuitous, and indestructible dignity no matter what they have done. It begins with the determination not to seek vengeance, not to respond to violence with violence. It means that however repulsive, foul, and personally injurious the enemy’s deeds are—whatever swirl of emotions and horrors they stir up, however revolted one feels by the very thought of them—one will firmly refuse to hate the person of the enemy. One endeavors to overcome hate with love. Self-defense does not require hate; it does not in itself constitute an act of violence against a person, even though the use of defensive force to stop the enemy may have the effect of causing physical harm to the enemy. But one must resist the inclination to choose for its own sake the harm the enemy suffers, to relish it, to permit it to become the motivation and driving force of self-defense.

This kind of disposition to love and forgive—this heroic non-violent interior discipline—is rarely found in its perfect form, but humans today should be able to see that it is worth pursuing as best as possible—even in the face of an invasion and the need for people to protect themselves, their communities, and their homeland by using physical “force” (which, in itself, is not violence) and even by fighting a defensive war. We must oppose the violence being perpetrated against us in ways that—even if they require the large employment of physical force—leave space for the enemy aggressor’s conversion, and at least do not conflict with the love that actively seeks their conversion, their abandonment of violence, and their willingness to change and—with sorrow—seek forgiveness and turn toward the work of restoring peace and amity. The alternative is the inevitable nurturing of resentment, enmity, counter-aggression, and the perpetuation of violence. Mutual atrocities and hatred will then be passed down the generations, and the cycle of violence will become more deeply impressed upon peoples who are supposed to live as neighbors. In the emerging epoch of power, entrenched mutual hatred endangers the survival of everyone. We have no choice but to begin to learn to govern our hearts with a more adequate and integral wisdom.

It is possible to forgive people from the heart while still holding them responsible for their evil acts, calling upon them to be converted, and to repair as much as they can the damage they have done. Crimes (and criminals) must also be punished by relevant political authorities in proportion to the harm they have inflicted on the common good. Forgiveness is a process that includes justice but that is also able to “surpass” it. It is a kind of “opening” for the transfiguring power of love—mercy—to touch people’s lives, to help the world, and initiate the miracle of healing. Only the redeeming love of Jesus Christ is capable of initiating this dynamic of forgiveness. Christ fulfills all justice, because He died on the Cross for every person and shed His blood to atone for every sin, our own sins and the sins our enemies (however awful they have been). The unity of the human race, and the true brother-and-sisterhood of every person, is founded upon and fulfilled only in the Heart of Jesus.

This confers no “bragging rights” on Christians; rather, it humbles us. We are charged to bear witness to Him—not to coerce, or exalt our peculiar human customs, or carry out violence in His name. It is a witness to the mysterious, pervasive, all-encompassing love of the One who has emptied Himself, poured Himself out in inexhaustible love for all of us. The Lord of History is Jesus, a man who allowed himself to become powerless, a man who died and forgave those who killed him. He rose from the dead, indeed, but with his wounds opened. He is Love. He does not work by violence. He loves. He is forgiveness.

We are a world at war—within ourselves, in our families, our communities, our workplaces, our polarized societies, politics, cultures, and—of course—in the overflow of rage and chaos that comes with the violence of nations attacking other nations, with weapons and destruction, atrocities and crimes against humanity, genocide. We cry out to the Lord to show us His unfathomable mercy, we cry out from the awful abyss of the horrors we have inflicted on one another and ourselves, from all the destruction we have wreaked that seems beyond anything we can do to repair it.

But God has come to dwell with us, to be with us even here (especially here!), to raise us from death to a new life, to reveal the glory of His Love that makes all things possible.

The forever “open” wounds of the Risen Jesus are our hope for true peace and reconciliation.